Summary of the paper: Anxiety Disorders, by Michelle G. Craske, Murray B. Stein, Thalia C. Eley, Mohammed R. Milad, Andrew Holmes, Ronald M. Rapee, and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen; (in press; 2017) Nature Reviews Disease Primers.

Precis by Ronald M Rapee, Centre for Emotional Health, Department of Psychology, Macquarie University.

In late 2016, several international researchers, who specialise in different aspects of anxiety disorders, were asked to prepare an update and overview of what we currently know about anxiety disorders for a major scientific journal – Nature Reviews Disease Primers. This update is highly technical and is aimed at scientists, therapists, and students. In the following article, I will provide a short summary of the key points from this paper, hopefully in a way that is more accessible to everyone. I won’t try and cover everything in the original review, but will focus on areas that I think will be of most interest to readers. Anyone who wants to read the original is encouraged to do so.

Introduction

The paper begins by pointing out that anxiety disorders include the largest group of mental disorders, are a serious source of disability, and cost our society a great deal (one study estimated that in 2010, approximately 60 million Europeans experienced anxiety disorders leading to a cost of over 74 billion Euros).

The paper begins by pointing out that anxiety disorders include the largest group of mental disorders, are a serious source of disability, and cost our society a great deal (one study estimated that in 2010, approximately 60 million Europeans experienced anxiety disorders leading to a cost of over 74 billion Euros).

The key features of anxiety include excessive and persistent fears along with extensive avoidance. Anxiety disorders often begin in childhood or adolescence and are typically long-lasting – without treatment, they can last for much of a person’s lifetime.

Importantly, anxiety is a normal emotion that varies in degree. Similarly, anxiety disorders can vary from mild to severe. In other words, people with anxiety disorders don’t “catch” some sort of “sickness” – rather, they differ from people without anxiety disorders simply in the extent or degree of their anxiousness and in the impact this has on their life. There is no simple cut-off point.

Statistics

The World Mental Health Survey is a large survey that measured the experience of a wide range of mental disorders from countries right across the world. They found that the chances of a person having an anxiety disorder at some point in their life ranged from 5% (China) to 31% (USA) with an average of 25%. In other words, on average, one person in four, will experience an anxiety disorder at some point in their life. Within a one-year period, an average of 12% of the world’s population has a diagnosable anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders typically start early in life and most people who are going to experience an anxiety disorder in their life, will already have one by their early adulthood. Like the other anxiety disorders, generalised anxiety disorder also often begins in childhood or adolescence, but it can start for the first time in adulthood or even older adulthood.

Some features increase the chances of people experiencing anxiety disorders. Females are approximately twice as likely as males to have an anxiety disorder. People who have a parent with an anxiety disorder are approximately 2-4 times more likely to also have one themselves. Experiencing stressful life events can increase the chances of having a later anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders are also more likely among people who were very shy and withdrawn in their early years, or who had a parent who was quite overprotective or negative.

People who have anxiety disorders, especially in their early years, are more likely to experience later depression and substance use problems.

Brain systems

The paper provided an overview of some of the latest understanding of the parts of the brain that underpin anxiety and fear and how these circuits work. I won’t try and summarise that here. However, a few interesting points can be summarised.

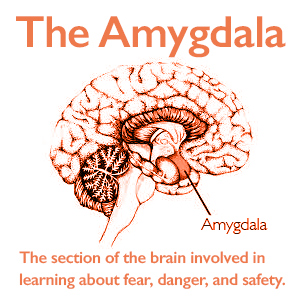

There have been some great advances in starting to identify some of the parts of the brain that are involved in experiencing fear and anxiety. One of the most widely discussed is called the amygdala, two areas deep in the brain that seems to be involved in learning about fear, danger, and safety and in helping to form fear memories. People with anxiety disorders seem to have a more reactive amygdala. More recent research is starting to identify important areas right across the brain that are involved in different aspects related to anxiety. One of the important findings is that these brain areas don’t seem to follow specific anxiety disorders. In other words, there isn’t a social anxiety part of the brain, and a separation anxiety part of the brain, and so on. This implies that the way that we talk about anxiety disorders in clinical practice, is not the way they are represented in the brain, and in the future, we will need to develop better ways of conceptualising these disorders.

Genes

One area where we have made huge advances in recent years is how our genes influence a range of issues and diseases. There is now no doubt that anxiety disorders are largely genetically affected. It seems that around 30-40% of the extent to which people vary in anxiety is genetic. The particular genes that are involved have not yet been identified and there are likely to be many, many of these.

One thing that is clear is that if genes affect up to 40% of the extent to which a person is anxious, then the environment must also be very important (up to 60%).

Current research is looking at ways in which genes and environments might work together. For example, a child who is genetically very shy and sensitive, might become a target for bullies. In turn, being bullied (part of the environment) might increase his/her anxiety.

Prevention

In more recent years, scientists have started to think that it might be possible to prevent people from developing problems with anxiety before they happen. There have been some real advances here – although we are still a long way from being able to properly prevent this problem.

One type of prevention has focused on teaching practical skills (such as problem-solving) to all of the children in a school year or even across a school. These programs are often delivered by the school teachers. Effects have been small, but nonetheless, these programs have started to show some real reduction in both anxiety and depression up to one year later.

Another form of prevention has tried to identify those children who might be at higher risk for later anxiety (and depression). As we mentioned above, two risk factors include having a shy, withdrawn temperament or having overprotective or negative interactions with parents. Very little research has been aimed at this form of prevention, but some results are very promising. In one of the biggest studies, teaching practical skills to the parents of very shy pre-school children, led to fewer anxiety and depression disorders 11 years later (when those children reached their middle teens).

A third type of prevention has focused on selecting those people (usually school-age) who are already showing some signs of anxiety. These studies are usually run in schools and use questionnaires to identify young people who have high(ish) anxiety, but not necessarily an anxiety disorder. These studies have shown some of the biggest effects that last up to one year later, but again, overall effects are not large.

Treatment

Treatments for anxiety have not changed dramatically in many years. But research continues to refine the treatments and to show which ones work. We now have a lot of evidence that cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) works very well for people with anxiety disorders at all ages (younger, adult, older adult). Following CBT around 50% of people with anxiety disorders reduce their symptoms to the level of the general population. Of course, even among the remaining 50%, many of them show very good improvements. Other forms of psychological treatment have not been shown to work as well. This doesn’t mean they won’t work for some individuals but, either we don’t yet have the evidence, or their effects in general seem smaller.

Medications for anxiety have also been widely tested and show good results. The most widely studied are the antidepressants, especially those referred to as SSRIs. These medications work well for anxiety and their effects are roughly similar to CBT. Other medications also work, especially one group referred to as benzodiazepines (one example is Valium). However, because they have a higher risk for abuse, they are usually recommended as a second choice.

Ending

The paper finished with a detailed look at some of the newer and more experimental areas that are being explored for anxiety disorders. There are new and exciting possibilities in understanding the mechanisms and causes of anxiety, in the prevention of anxiety, and in its treatment. At this stage few of these directions has yet built up enough evidence to use them in any meaningful way or to recommend them to the public. The main exception is the use of distance therapies – that is, CBT that is run over the internet, via telephone, or through apps. These methods of distributing treatment are starting to be very well tested and they seem to show effects that are as good, or almost as good, as CBT in a therapist’s office. Their two biggest advantages are 1) they can be delivered to people anywhere (including rural and remote parts of Australia), and 2) they usually require less time from a therapist making them cheaper and easier to use within our public health systems.